Amidst the shock and awe of the U.S. siege in Venezuela, federal immigration police occupying Minneapolis, and the potential dissolution of the post-World War II international order, the steady climb in food prices has not garnered much media attention. But rest assured, to those feeling pain in the checkout lane, you are not alone.

On January 13, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that food prices rose 3.1% in the twelve months leading up to December 2025. More concerning, December’s 0.7% increase, the largest single month rise since October 2022, suggests that grocery price inflation may be accelerating. Unfortunately, federal policy seems likely to push prices even higher.

Most directly, tariffs are adding to grocery bills. A study of 25 million shipment records released earlier this week concluded that foreign exporters passed along 96% of the new tariff burden to consumers. Effectively a $200 billion federal sales tax, the tariffs help to explain the sticker shock on items like coffee, whose prices soared after the Administration slapped tariffs as high as 50% on major importing countries like Brazil. The U.S. Supreme Court may soon strike down the Administration’s “emergency” tariffs, but the U.S. Trade Representative has said that it will enact new tariffs using alternative authorities if that’s the case.

Another policy driving up food prices is immigration enforcement. Notably, prices for “food away from home” rose by significantly more (4.1%) in 2025 than “food at home” (2.4%). That reflects the higher proportion of labor cost in the price of prepared food.

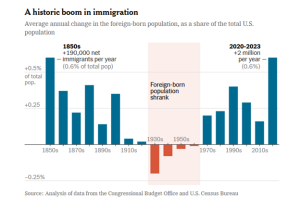

Unlike tariffs, for which voters never expressed much enthusiasm, concerns about immigration accounted for much of President Trump’s popularity in the 2024 election, with Trump voters ranking it as their most important issue, ahead of the economy. The graph below from The New York Times illustrates the increase in immigration that preceded the recent immigration crackdown.

The boom is over. Recent estimates indicate that net migration in 2025 was negative for the first time in half a century, with between 10,000 an 295,000 more people leaving than entering the country.

This will have a significant effect on food prices. According to one recent analysis, if fully realized as proposed, the Administration’s immigration policies could result in American families paying an additional $2,150 for goods and services each year by the end of 2028. The “services” of course include “away from home” meals , with immigrants making up an estimated 22% of restaurant workers (and more than 30% in states such as California, New York, and Texas). Other sectors of the food economy depend even more on immigrants. As the Administration has stripped away the legal status of 1.6 million people, many of these workers find themselves ineligible to continue in their jobs. But ICE is also targeting workers whose lawfully issued work permits remain valid, such as those awaiting adjudication of asylum claims. Striving to meet arbitrary arrest quotas, ICE agents have taken to detaining their waitstaff after dining out.

With fewer available workers, restaurants and the rest of the food industry have to offer more compensation to attract staff, and the costs gets passed to consumers. Businesses are feeling the strain, prompting Republican lawmakers to express support for immigration reforms designed to protect the supply of cheap labor to agriculture and other sectors that have historically struggled to entice American workers. But even if congressional leaders exceed all expectations in passing reforms to counter the current labor exodus, the Administration’s immigration policy threatens to inflate food prices in a more fundamental, insidious way.

International trade and immigrant labor aside, America has flourished because of its ideals. Despite many glaring contradictions, the country blazed a trail in establishing the rule of law above the rule of kings or emperors, and that tradition has created unprecedented prosperity. Over two centuries after George Washington shocked the world by stepping down from power voluntarily, we take for granted that the highway patrol officer will not solicit a bribe when she pulls us over for speeding, or that the magistrate judge will not throw out our lawsuit because he is a member of the opposite political party.

Citizens of other countries have not had the same institutional stability, and they have suffered economically as a result. As the 2024 Nobel Laureates in economics explain “poor rule of law and institutions that exploit the population do not generate growth or change for the better.” So when U.S. leaders take actions that undermine the rule of law, they also undermine economic prosperity. In this way, ICE seems poised to make us all a lot poorer, and not just because farmers cannot find anyone to pick strawberries.

With the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” Congress has made ICE the country’s highest-funded U.S. law enforcement agency, with a budget that exceeds most of the world’s militaries. The litany of ICE abuses perpetrated on foreign nationals and citizens alike (including local police officers) could fill many blog posts. One in particular has grabbed the nation’s attention: the killing of Renee Good. The Administration has responded to her killing with brazen lies followed by an investigation into the victim’s widow, but not the officer. Even those inclined to think the officer that killed Good was somehow justified in shooting her should find the Administration’s persistence in labeling Good a “domestic terrorist” profoundly disturbing. Likewise the news that ICE has been secretly instructing agents to ignore the 4th Amendment’s protection against warrantless searches.

As ICE continues to add officers, more abuses are sure to follow. The Administration and its allies in an historically inactive Congress show no signs of letting up. A week ago, the Century Foundation issued its latest “Democracy Meter.” It makes for grim reading:

“The U.S. government has become more authoritarian in its intentions and its practices, even if it cannot always achieve its authoritarian goals… Congress and the judiciary, already weak as noted above, failed to check the executive branch when it disregarded constitutional checks and balances, ignored court rulings, and engaged in grand corruption—an unprecedented breakdown of the law and the constitutional order in the United States.”

This breakdown will reverberate for years to come, and hamper economic growth, including by driving up food prices, as a previous CFA blog explained.

Fortunately, the U.S. has strengths that set it apart from so many other countries that have succumbed to democratic backsliding. The federalist system complicates any totalitarian project. Responsibility for elections is widely dispersed among state and local officials, many of whom will refuse to be complicit in overturning the will of voters, regardless of their party affiliation. Most importantly, Americans do not have a tradition of bowing to strongmen, and show every sign that they will continue to make their voices heard, despite the mounting risk.