If the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) were to close its doors today, 836,588 Americans would be left waiting for an answer to the complaints they have filed with the CFPB. According to records in the still-operating CFPB Complaint Database, these complaints are labeled “in progress.” In essence, they have been filed, but not resolved.

There is work to do. Why isn’t it being done? Because CFPB Acting Director Russ Vought intends to illegally eviscerate the agency, rendering it without the funds it needs to operate. The CFPB is running out of money, simply because Vought will not request a transfer from the Federal Reserve. By law, the CFPB receives funding from the Federal Reserve’s revenues; the Director needs merely to request a draw.

This dubious budget shortfall is a problem of Vought’s making. Before the start of the year, the CFPB drew up a 2025 budget of $823 million. The Big Beautiful Bill reduced available funds by slightly less than half. Since taking office, Vought has not made any requests, resulting in a steady depletion of the CFPB’s resources. It is entirely possible that the CFPB could run out of money in a few weeks, and the chance it lasts through January, absent an intervention requiring Vought to seek funds, is very much in doubt.

How the Complaint System Works

The CFPB’s complaint database is a powerful tool mandated by statute: the CFPB must accept complaints, forward them to financial companies, and follow up. The CFPB’s complaint database democratizes regulations by giving people the power to fight back when financial institutions refuse to address their concerns. Anyone who has ever called their bank with a concern understands the problem. Unlike for the average consumer, banks cannot put a CFPB complaint on hold. They have to respond. Complaints received by the CFPB are forwarded to the company at issue, which then contacts the consumer. Resolution is supposed to occur promptly. The CFPB records one of five outcomes: closed with monetary relief, closed with non-monetary relief, closed with an explanation, untimely response, or in progress. Closed with an explanation means the company denied relief.

In practice, the CFPB expects a response in 15 days, and 99.7 percent of complaints received a timely response in 2024. The difference now is that companies, rather than responding quickly with a yes, are saying “no” more often because they realize the CFPB has lost its bite.

Additionally, the CFPB uses complaints to identify trends and flag potential problems. Those data points inform supervision and enforcement efforts. Complaints are a significant resource for holding the companies supervised by the CFPB accountable. Additionally, the CFPB forwards complaints to other agencies when appropriate. Because the public can access complaint data, the database serves everyone’s interests.

Recent complaint data tells two important stories. First, many complaints remain unresolved. Second, financial institutions (FIs) have become less responsive to complaints.

The volume of complaints suggests that frustrations with financial institutions are increasing.

Despite moves to decimate the agency and humiliate its staff, the American people still rely on the CFPB when they have a problem with their financial institution. The following chart documents the rapid increase in complaints filed with the CFPB. Nearly half of all complaints ever filed with the CFPB have been received in the last 12 months.

These numbers show the contradiction between Russ Vought’s actions and the needs of Americans who want their government to work for them. Vought isn’t requesting funds from the Federal Reserve to fulfill the agency’s mission, even though people clearly want and need the agency’s help. Indeed, of the more than 12.6 million complaints filed since the CFPB opened its doors, 43.3 percent were filed in the last 12 months. Not only does this result reflect the public’s awareness of and trust in the database, but it also demonstrates that the zeal for deregulation is directly affecting household finances. Drilling down to the backlog of complaints, it is easy to see a pattern. Of the unresolved complaints, over 97 percent came in after Russ Vought became the CFPB’s Acting Director on February 7th, 2025.

The Complaint Database shows that financial institutions are increasingly unlikely to grant relief.

The likelihood that a complaint will result in relief has steadily declined. During the prior administration, roughly half of the complaints resulted in some form of relief. Relief may take the form of compensation or the rectification of a mistake.

Beginning in mid-summer, the likelihood of relief declined precipitously. By November 2025, fewer than 5 percent of cases resulted in relief. So far this month, fewer than 1 percent have had such an outcome. Financial institutions have concluded that no one will hold them accountable if they ignore the concerns of upset customers.

This Fall, FIs became much more likely to deny relief.

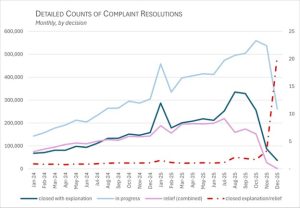

While there is some lag between the issuance of a complaint and a resolution, early returns show that FIs are much less likely to grant relief. Historically, fewer than half of complaints have resulted in either kind of relief. While the number of complaints fluctuated month to month, the share of complaints closed with an explanation (no relief) usually outnumbered those with relief by 1.1:1. But beginning in August 2025, the numbers started to shift. That month, the ratio exceeded 2 to 1, jumped to 3.2 to 1 in November, and has exceeded 20 to 1 in December.

The red dotted line shows the ratio of complaints closed with an explanation over complaints closed with relief. When the ratio increases, it means that a higher ratio of complaints is being closed with explanations – meaning no relief – versus those receiving relief. The dramatic increase in the ratio suggests that financial companies now feel emboldened to ignore consumer complaints.

The numbers refute the CFPB’s argument that it is prioritizing the needs of servicemembers.

Complaints filed by servicemembers that are not yet resolved now exceed 8,400.

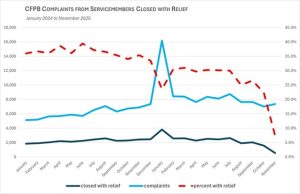

Although the agency has largely suspended enforcement and curtailed supervision, the CFPB says it prioritizes servicemembers. Yet despite those promises, under this administration, that is not always the case when they have a problem. The chart below shows the monthly volume of complaints filed by servicemembers, the number closed with relief, and the percentage of those closed with relief. Although the number of complaints filed by servicemembers remains within recent norms, the number resulting in relief has declined.

The spike in complaints followed the CFPB’s enforcement action against Navy Federal Credit Union. News of the settlement prompted many servicemembers to lodge complaints with the CFPB, believing their frustrations were finally being addressed. Of course, their hopes were dashed when the CFPB dropped its order shortly after the new administration took over.

Servicemembers are less likely to receive relief (monetary or non-monetary) now than in the prior administration, and the rate of relief continues to fall. Year over year for November, the likelihood that a servicemember received relief fell from 35.4 percent to 7.4 percent. Through December 17th, the rate had dropped further, to 2.2 percent.

Conclusion

These numbers underscore what has been lost with the attacks on the CFPB’s authority. The surge in complaints reflects ongoing consumer frustration with their financial institutions. And the declining rates of relief show how dramatically the new leadership at the CFPB has walked away from its obligations. Financial companies know the financial protection security desk is now unmanned and therefore no longer feel accountable. The complaint database – one of the ways the CFPB has alerted the public about problems in financial services – is now sending a message to the public that the leaders of an agency charged with protecting their finances no longer care about their needs.