Washington, D.C. – California’s insurance consumer protection law, known as Proposition 103, continues to provide against-the-grain savings for California drivers, according to new data released by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC). The NAIC’s recently issued “State Auto Insurance Report 2010/2011” shows that California once again bucked the national trend as residents’ average auto insurance expenditures declined in 2011, while they rose nationally. The new 2011 data saw California rates drop by another 1 percent as national rates rose by 1 percent. Over the past five years, Californians have enjoyed a 9% reduction even as auto insurance prices have remained flat countrywide. California motorists spent about $340 million less in 2011 than they would have if California premiums had instead followed the national trend.

The latest NAIC data confirm a report issued last November by Consumer Federation of America (CFA), detailing more than $100 billion in savings for California drivers over the past 25 years as a result of Proposition 103, the 1988 ballot initiative approved by California voters that established strong consumer protections and reformed the property-casualty insurance industry. Using previous NAIC data, CFA concluded that between 1989 and 2010, auto insurance premiums actually dropped by 0.3%, while they rose 43.3% nationally during that period. California was the only state in the nation where prices dropped over the 22 year period.

The new NAIC data also counter a recent critique of the CFA report to which the industry trade newsletter Auto Insurance Report (AIR) dedicated its entire final issue of 2013. The AIR story was authored by the newsletter’s writer, Brian Sullivan, who asserts that California’s unique rate reductions over the last 25 years were the result of a court decision and unidentified “unforeseen forces” but not Proposition 103.

A similarly-themed opinion article by longtime California insurance lobbyist Bill Gausewitz appeared in Insurance Journal (IJ), another trade magazine, several weeks later. According to CFA’s Insurance Director Bob Hunter, an actuary and former Texas Insurance Commissioner, the new data show that the twin industry reports are biased and unreliable.

“The insurance industry is desperate to convince regulators, lawmakers and the public that California’s consumer protections don’t lower insurance rates, even in the face of overwhelming data, from over twenty-two years, that show significant savings,” said Hunter. “The AIR story largely repeats several other attempts at misdirection unleashed by the industry to obscure the facts CFA detailed in its report last November. But even the AIR publication was forced to admit that Proposition 103’s anti-discrimination efforts have worked to protect consumers from unfair prices, a conclusion we share and highlighted in our report.”

Flawed Industry Analysis Ignores Data, Makes Unsupported Claims

CFA has reviewed the AIR claims, revealing several errors in the analysis, including, significantly, Sullivan’s decision to ignore the most recent three years of data when calculating the long-term impact of Proposition 103.

Below, CFA details the selective use of data and the various unsupported claims and opinions-presented-as-facts in the AIR and IJ publications:

AIR uses data selectively, arbitrarily ignoring at least three years of data, to assert that premiums only fell compared to the nation in the first decade after Proposition 103 was passed but rose compared to the nation in the next decade. AIR claims this shows that tort-law restrictions, not Proposition 103, probably caused the savings. For some unexplained reason, AIR cherry picked the time periods studied for price change by excluding widely available data for 2008-2010. AIR split the years 19892007 into two equal periods (1989 to 1998 and 1998 to 2007) and claimed California’s premiums were lower only in the first period not the second. If, instead, he used all the data, he would have found that California beat the nation in both periods.

Further splitting the data into three equal but shorter periods, as shown below, confirms California’s unique savings compared to the nation in all periods.

| Year | California Avg. Expend. | Countrywide Avg. Expend. |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | $747.97 | $551.95 |

| 1996 | $799.04 | $691.32 |

| 2003 | $837.30 | $824.49 |

| 2010 | $745.74 | $791.22 |

| Change ’89 – ’96 | 6.8% | 25.3% |

| Change ’96 – ’03 | 4.8% | 19.3% |

| Change ’03 – ’10 | -10.9% | -4.0% |

If Sullivan used the newly available 2011 NAIC data, the ongoing distinction between California’s falling premiums and the nation’s rising premiums would be confirmed and amplified. Only by arbitrarily selecting periods and refusing to use all available data, could Sullivan calculate his misleading finding.

Claims that a court decision or some other “unforeseen force” led to a massive onetime change for Californians and that Prop 103 had little or no effect on prices are unsupported and demonstrably incorrect. AIR (and Gausewitz in IJ) makes one primary argument: the lower premiums realized in California were not because of Prop. 103 but “because of Moradi-Shalal or some other unforeseen force.” Putting aside the specter of an “unforeseen force” (which AIR never identifies) that lowers insurance premiums by billions of dollars, we focus in on the industry theory that Moradi-Shalal provided Californians savings for a limited time and then California returned to national trends. Moradi-Shalal is a 1988 California Supreme Court decision that prohibits drivers from suing the auto insurance company of an at-fault driver. Known as a restriction on “third-party bad faith lawsuits,” Sullivan theorizes that all savings in California between 1989 and 1998 are the result of reduced payouts by insurance companies as a result of the Supreme Court decision limiting such lawsuits. The argument does not withstand scrutiny.

- Sullivan argues that all the savings identified by CFA happen within ten years of both the Moradi-Shalal decision and Prop 103’s enactment and that if Prop 103 was the source of savings, California would continue to stand out from the nation, while if the source was the Court decision there would be something more like a one time savings and then California would follow national patterns. As described above, objectively documented in the CFA report, and confirmed by new NAIC data, California continues to stand out and defy national trends twenty-five years after passage of Prop 103. AIR’s claim that California is only better than the nation immediately after the Court decision relies entirely on cherry-picked data and ignores more recent information.

- AIR provides no evidence – there is none – that it took ten years for insurers to adapt to Moradi-Shalal. Other than outstanding claims that were pending in the courts prior to the Supreme Court’s decision, the right of third parties to sue an insurance company for bad faith was terminated in 1988, so the change would be reflected in insurance rates very quickly after the ruling. There is no rational basis for the suggestion it took ten years. In fact, the data show that the differences between auto insurance premiums in California and the rest of the nation started accruing several years after the Moradi-Shalal decision corresponding to the period when Proposition 103’s rate refunds began to be issued and the prior approval system was implemented. (Whereas the Moradi decision took immediate effect in 1988, Prop 103 endured nearly 100 unsuccessful insurance industry lawsuits and several years of hearings and other steps toward implementation of the regulations before its full effect was realized.)

- AIR ignores the fact that most states have restrictions on third party bad faith lawsuits similar to those that have been in place in California since 1988. Therefore, under the AIR theory, California should be no different than the countrywide average change in auto insurance prices, at least once the state’s insurers responded to the 1988 Court decision, yet California consistently provides better-than-the nation results, as confirmed once more in the new NAIC data. As the CFA report highlights, several states with similar Moradi-type restrictions as California’s have seen dramatic increases in insurance rates at the same time California premiums have fallen. Thus, the Moradi decision cannot explain California’s unique results.

- Unable to explain California’s unique drop in comprehensive insurance costs, a coverage for which consumers maintain the same right to sue as they had prior to Moradi-Shalal, AIR suggests – without offering any support – that the “most likely explanation for California comprehensive premiums rising more slowly than the rest of the nation relates to the extraordinary run of weather events in the middle of the country over the past decade.” Once again, the logic fails. US comprehensive premiums went up 35% nationally since 1989, while in California the premiums dropped by 17%. Weather in the middle of the country might theoretically explain a “slower rise” in premiums in California than in the middle of the nation, but certainly not a 17% price cut in California!

- Finally, AIR alleges that claims paid in California have fallen, while those paid nationally have risen since the legal restrictions took effect. He provides no support, however, for his argument that the fall in claims payments has to do with Moradi-Shalal, as opposed to the new and substantial incentives that Proposition 103 created to improve driving safety on an ongoing basis. According to NHTSA data, California represented about 10.6% of the nation’s fatal crashes in 1992, but only 8.5% in 2012. Similarly, the fatality rates per vehicle miles traveled have fallen faster in California than nationally under Proposition 103, with fatalities per 100 million miles traveled in California down 46% since 1992 compared with 37% nationally. Proposition 103 has several rules that significantly incentivize safe driving and deter unsafe driving, including a 20% discount for “good drivers;” a mandate that driving records have the most impact (good or bad) on customers’ premiums; incentives to reduce annual mileage (and thus reduce accident risk); a good driver protection giving the good driver the absolute right to get insurance from any insurer he or she selects; and a requirement that the good driver be offered the very lowest price that exists in the entire insurer group when a quote is sought.To ignore these unique loss mitigation incentives of Prop 103, as AIR and the industry cohort do and ascribe all savings to a limit on certain lawsuits for insurance bad faith is indefensible.

The AIR critique of higher than average industry profits in California confirms CFA’s critique, but fails to note that the too-high profits were accrued during the years when Proposition 103 was overseen by insurance industry-affiliated

Commissioners who failed to regulate the companies. On several occasions, including its most recent report, CFA has identified California’s higher-than-average industry profitability as evidence that even more savings could be won for consumers under Proposition 103. In response to the industry/AIR critique, CFA conducted a more thorough analysis of the industry’s rate of return (ROR) in California.

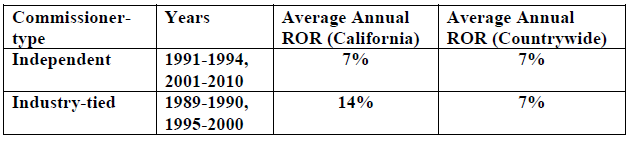

Between 1989 and 2010, the ROR for auto insurance companies in California averaged 10%, while the national ROR averaged 7%. However, after a more detailed look at annual profits during the Proposition 103 era, we find that industry profits in California have matched the national average when the analysis excludes profits earned during the regimes of the explicitly pro-industry Commissioners. These include 1989-1990, the years of the last appointed commissioner, Roxani Gillespie (Prop 103 made the Commissioner an elected post after 1990), who has been an attorney for insurance companies since leaving office, and the administration of Commissioner Chuck Quackenbush (1995-2000). Quackenbush resigned in disgrace in 2000 while facing a likely impeachment related to his insurance industry fundraising, among other issues. All told, Quackenbush reportedly accepted approximately eight million dollars in campaign contributions from insurance industry sources; no other elected California commissioner has accepted any insurance industry contributions. We found that profits in California under independent regulators (both Democrat and Republican) were in line with national average profits, as shown below:

This finding reveals that Proposition 103, like any consumer protection law, requires implementation by independent, public-oriented regulators in order to fully achieve the law’s protections. It also illustrates that consumer protection laws like Proposition 103 allow companies reasonable and standard profitability while still achieving savings for consumers.

AIR makes the paradoxical and bizarre claim that California is not competitive because Progressive and GEICO do not have as much market share in the state as they do nationally. AIR’s apparent admiration for these two companies does not translate to support for the opinion that California is not a competitive insurance marketplace. Nor does it provide any basis for AIR’s dismissal of a widely accepted index of competition that shows California is a highly competitive marketplace. There are three key points to be made here.

- The fact that California has such a competitive market is a key reason that these two major insurers do not have as much market power in the state as they do nationally. According to market concentration measures3, California hosts the fifth most competitive auto insurance market in the nation. California has more than twenty insurance groups writing at least $100 million in auto insurance each year. GEICO ($1.1 billion, 5.8% market share) and Progressive ($800 million, 4.1%) hold places seven and nine, respectively. Just ahead of these goliaths are Auto Club of Northern California (7.0% share), Mercury (8.5%) and Auto Club of Southern California (8.7%). Indeed, none of California’s largest groups – Zurich/Farmers (13.99%) and State Farm (13.8%) – exceed a 14% share of the market. That California has several name-brand alternatives to the big three (Farmers, State Farm and Allstate) is more proof of a competitive market than GEICO and Progressive’s inability to control the market proves otherwise.

- A second important reason that GEICO and Progressive are not as big in California as they are elsewhere lies with California’s unique set of consumer protections. Under California law, insurers must base premiums primarily on driving safety record, miles driven annually and years of driving experience. GEICO and Progressive, more than most insurers, have built their business around pricing practices that rely on social status factors such as credit score, education, occupation and prior insurance history that California law prohibits as unfairly discriminatory. California’s strong anti-discrimination laws may simply make the state not as attractive to these two insurers and other insurers who rely on non-driving-related factors that tend to drive up prices unfairly on low- and moderate-income drivers.

- Finally, AIR ignores the fact that California is the only state that requires equal access to the competitive market for consumers by giving good drivers the right to get the lowest priced insurance from the insurer of their choice under Prop. 103’s good driver protections, guaranteeing competitive balance between demand (motorists must buy state required auto insurance) and supply (insurers in California must sell auto insurance to all who wish to purchase). Further, California enforces antitrust laws against insurers, while in all other states the industry is either entirely or largely exempt from antitrust scrutiny. Progressive and GEICO may not be able to compete in such a truly competitive climate.

Correlation and causation: AIR and Gausewitz contradict their own methodologies and accidentally step into debate on credit scoring

- The recent industry articles in AIR and IJ both criticize CFA’s report for detailing a statistical correlation linking Proposition 103 to the lower rates in California since its passage. Both suggest, as lobbyist Gausewitz writes, that “this conclusion violates the fundamental statistical rule that correlation does not imply causation” and AIR states, “correlation is not causation.” However, both rely on unsupported correlations to defend their alternative theory for lowered rates in California. Perhaps more interestingly, Sullivan, in AIR, uses his article to criticize California law for prohibiting the use of credit score based auto insurance premiums, which is a glaring example of the use of alleged correlations for pricing, despite any credible argument for causation. If Sullivan and Gausewitz are so deeply concerned with proving causation rather than relying on correlation, we wonder if (though highly doubt) they would retract their support for credit scoring and other pricing factors for which there is no evidence of causation.

A few points of near agreement

In his article for AIR, Sullivan is compelled to acknowledge some points with which CFA agrees. In particular, Sullivan notes that “Prop. 103 forced prices down” and incentivized insurers to “boost fraud-fighting efforts” but decides that these effects are unquantifiable and therefore ignores them when drawing conclusions about the law’s impact on prices. Sullivan concludes by saying, “Californians seem to like their (Prop. 103) rules…” With this, we agree. Further, CFA believes, and national surveys CFA has conducted in recent years confirm, that citizens around the country will feel the same when consumer protection reforms like Proposition 103 are adopted in their states.