Washington, DC. – Most drivers are not offered significant price breaks for cutting down on their driving, Consumer Federation of America (CFA) reported today. New research found that in the 11 cities tested outside of California, the nation’s largest auto insurers generally offered little or no premium reduction to low-mileage drivers compared with high-mileage drivers, even though insurance research indicates that how much you drive is among the most important factors in predicting accidents. According to the research, Progressive and Farmers usually charge the same rates to someone who drives only 2,500 miles a year as they charge someone else who drives 22,500 miles a year – nine times as far – all else being equal. CFA noted that, in setting customers’ premiums, insurance companies often give more weight to personal characteristics such as marital status and credit score than to key risk indicators such as mileage driven annually.

After reviewing 275 quotes for basic liability coverage from five large insurers, CFA found:

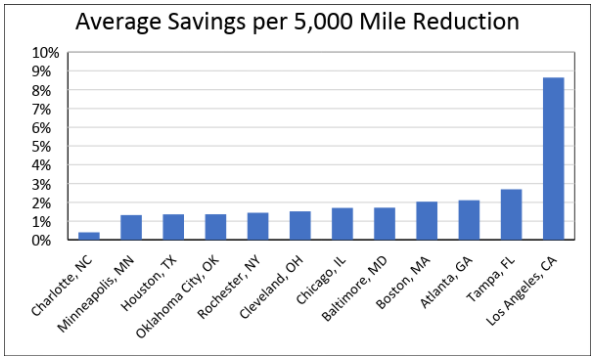

- Consumers save only $30 per year, or 1.6%, on average for every 5,000 fewer miles driven annually, excluding California drivers, who save $81 on average, or 8.7%.

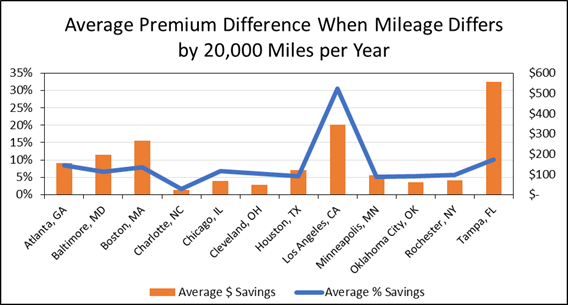

- Outside of California, premiums for very low-mileage drivers (2,500 miles/year) are only $102 lower*, on average, than very high-mileage drivers (22,500 miles/year), a savings of about 6% annually. (*Excludes Allstate in Tampa, where minimum coverage quote was not provided.)

- In Los Angeles, very low-mileage drivers save $346, or 30%, compared to very high-mileage drivers.

- Outside of California, Farmers and Progressive provide no mileage-based savings in tested cities, Geico offers a small price reduction, while Allstate’s and State Farm’s lowest-mileage customers saw average savings of 11% and 13%, respectively, compared with the highest-mileage drivers.

“How well you drive and how much you drive should be the primary factors considered when insurance companies set premiums, but we have found that many companies either entirely ignore their customers’ actual mileage or give such a pittance for low-mileage as to have no meaningful impact on rates,” said J. Robert Hunter, CFA’s Director of Insurance and former Texas Insurance Commissioner. “For people in most parts of the country, with California as the notable exception, you’ll often pay about the same auto insurance premium whether you commute 90 miles round trip every day or if you take public transit to work and only drive on the weekends. If you drive less, you should pay less, because you can’t crash when you’re not driving.”

When insurance companies diminish the impact of mileage in their pricing methods, lower-mileage drivers are punished for reducing their risk by having to overpay for coverage, according to CFA.

For its research, CFA sought online premium quotes for basic liability coverage from Allstate, Farmers, Geico, Progressive, and State Farm for a driver with an unblemished record in which the only difference between in each quote was the number of miles driven; CFA sought five different quotes in 5,000-mile increments between 2,500 and 22,500 miles annually per company in each of the 12 cities tested. The cities tested were: Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, Charlotte, Chicago, Cleveland, Houston, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, Oklahoma City, Rochester (NY), and Tampa. The full set of premium quotes are in the Appendix.

California is the Exception to Unfair Rates, Where Consumer Protection Rules Require Insurers to Charge Lower-Mileage Drivers Less

Among the twelve cities tested by CFA, only drivers in Los Angeles, California saw consistent savings for lower mileage driving, with premiums dropping by an average of 8.7% for every reduction of 5,000 miles per year and very low-mileage drivers paying 30% less than very high-mileage drivers. Under California law, auto insurers are required to give drivers’ annual mileage the second most weight when determining their premiums, with driving record being given the most weight.

Drivers in other cities see average savings of only about 1.6% for every 5,000-mile annual reduction, which amounts to less than $3 savings per month:

- Motorists in Charlotte, Minneapolis, Houston, Oklahoma City, Rochester, and Cleveland see a mere 1.5% or lower savings for mileage reduction;

- Chicago and Baltimore drivers receive less than 2% savings; and

- Drivers in Boston, Atlanta and Tampa earn less than 3% for scaling back their mileage.

Even huge drops in annual mileage yield only minor premium savings in most parts of the country. CFA compared motorists who drive 2,500 miles per year with those who drove 22,500 miles per year and found surprisingly limited benefits to most drivers tested. Only about a quarter of drivers outside of California would receive a 10% cut and in only one of 50 tests outside of California did a driver receive 20% savings or more for driving 20,000 miles less than another driver. Savings for the very low-mileage drivers were over 28% from four of five companies in California.

*The relatively large premium savings for low-mileage driving in Tampa – $556 per year – mainly reflects the fact that Allstate.com quotes are extremely high for all drivers (between $6,172 and $8,046 per year) and are for higher than minimum limits coverage as the company website does not provide minimum coverage quotes online.

Insurance Companies Acknowledge Impact of Miles on Insurance Risk but Often Don’t Provide Consumers the Benefit

While all five companies provide discounts for lower mileage driving in California, the companies track record in other states is much worse, as shown below:

| Company | 11 Cities (excl. LA) | Los Angeles |

|---|---|---|

| Allstate | 2.9% | 10.6% |

| Farmers | 0% | 7.7% |

| Geico | 1.3% | 12.6% |

| Progressive | 0% | 9.4% |

| State Farm | 3.2% | 2.9% |

The fact that insurers don’t give much benefit to drivers for reducing risk by reducing the miles they drive contrasts with company website statements that explain why lower-mileage drivers should see savings. For example:

- State Farm: “The more miles you drive in a year, the higher the chances of a crash – regardless of how safe a driver you are…Consider joining a car or van pool, riding your bike, or taking public transportation to work. If you reduce your total annual driving mileage enough, you may lower your premiums.”

- Allstate: “Insurers typically look at how much you use your car. Someone who has a long commute to work may pay more for insurance than someone who only uses their vehicle to run errands on weekends — since more miles behind the wheel mean more exposure to risk.”

- Geico: “How much you drive each year can increase your auto insurance rates because it places you more at risk of being involved in an accident. People who drive fewer miles than average are usually eligible for lower rates on their auto insurance.”

- Farmers: “Driving less could save you a bundle not only on gas but also on your premium. If it’s an option, try moving closer to work or carpooling. Infrequent drivers are at a lower risk of being involved in an accident, and may therefore enjoy low-mileage discounts.”

- Progressive, singularly, acknowledges that it doesn’t differentiate between low- and high-mileage drivers (“In the large majority of states, we won’t even ask about your mileage. You’ll pay the same rate whether you drive 50 or 5,000 miles a week!”). Instead, Progressive solicits customers to sign up for its driving monitoring program that, the company claims, measures drivers’ hard braking, late night driving, and miles driven. The company provides a 0% to 15% discount to participants in the program.

“The insurance industry knows that how many miles people drive each year is directly related to their risk of being in an accident, but companies consistently ignore this and charge drivers higher rates even when they are lower risks,” said insurance expert Douglas Heller, who conducted the analysis with CFA researcher Michelle Styczynski. “At the same time, many of these companies feel perfectly at ease charging lower-income drivers with perfect records higher rates than well-to-do customers based on factors like their job title, education level, credit score, and whether they rent or own their home.”

CFA Calls on State Lawmakers and Insurance Commissioners to Demand that Auto Insurance Rates are More Closely Tied to Drivers’ Mileage

Because insurers are not consistently providing reasonable premium reductions for the reduced risk of driving less, policymakers and commissioners should require that companies do so. As a matter of state law, drivers in every state except New Hampshire are required to purchase coverage from auto insurers, so there is a special obligation on state governments to ensure fairness in pricing. Whether it is a commissioner who orders a company to recraft their rating methods to increase the impact of mileage on customer premiums or lawmakers enacting legislation that increases the weight given to mileage, it is clear that state action is needed to curb industry practices, according to CFA.

“Precisely how much premiums should fall when a driver decides to carpool to work instead of always driving themselves is a reasonable actuarial exercise but charging the same amount to a 5,000-mile driver and a 20,000-mile driver is undeniably unfair,” said CFA’s Hunter. “Since insurers won’t give low-risk drivers a break, consumer protection rules should require it.”

Insurer Complaint that Mileage Estimates are Not Useful Doesn’t Hold Up

Some insurers, including Progressive, argue that companies don’t emphasize mileage when setting rates “because drivers commonly overestimate and underestimate how much they drive.” But there are several ways by which insurers confirm the accuracy of mileage estimates, including recording odometer readings at the times of policy purchase, policy renewal, and accident claims. These readings can be taken not only by company agents but also by third parties such as auto repair shops and other data suppliers. In fact, CARFAX maintains a database on the odometer readings of tens of millions of vehicles, which is based on information from more than 90,000 sources – dealerships, departments of motor vehicles, police and fire departments, rental car companies, and auto repair shops, that insurers use to collect data on their customers. Those states requiring periodic safety and/or emission inspections represent an especially useful source of odometer readings. All these sources can be used to check and, if necessary, correct driver mileage estimates.

Research Clearly Establishes Strong Relationship Between Mileage and Insurer Losses

Actuarial research consistently shows a strong relationship between mileage and insurance claims:

- A 2009 study by Quality Planning, a company providing data to auto insurers, based on about 500,000 insurance policies, found that the lowest annual mileage group (0-3,000 miles) had 44 percent fewer claims than the average, while the highest annual mileage group (more than 20,000 miles) had 28 percent more claims.

- A 2012 Wharton School Working Paper – “The Use of Annual Mileage as a Rating Variable” by Jean Lemaire, Sojung Park, and Kili Wang in – concluded that “annual mileage is an extremely powerful predictor of the number of claims at-fault.”

- In an analysis of nearly three million car years based on 2006 data from the Massachusetts Commonwealth Automobile Reinsurer, MIT’s Joseph Ferreira and Eric Minikel learned that an increase in annual mileage from 10,000 to 30,000 increased claim frequency by 60 percent and claim costs by 43 percent.

- And, in a study matching mileage readings collected during emission checks in the Vancouver area with insurance claims records for more than 500,000 vehicle-years, Todd Litman of the Victoria Transport Policy Institute found that increasing mileage from less than 5,000 kilometers/year to 20,000-25,000 km/year doubled crash rates.