By: Sara Geoghegan, EPIC and Ben Winters, CFA

(This blog is cross-posted on both sites)

Takeaways:

- Browsing, purchasing, and location data that people create in the process of seeking care are all sold by data brokers to advertisers, scammers, and more

- Hospital, insurance, and prescription discount websites have all tracked users’ activity on their sites, with tracking pixels associated with Google, Meta, and Microsoft

- Data broker profiles contain information used to categorize individuals into “segments” like health characteristics, such as “likelihood of having anxiety,” “diabetes,” “bladder control issues,” “frequent headaches,” and “high blood pressure”

- AI systems are asking for personal health documents and injecting questionable medical advice into many systems people use daily

In an era of maximization of data collection, consumers are left to rely on walls of pop-ups and click-throughs as well as broad promises about companies “caring about privacy.” When you track your steps, google your symptoms, or check the price of a prescription, you shouldn’t have to worry about which companies can access and exploit this information in ways that may be completely unrelated to its original purpose.

Recent news includes a near constant parade of concerning uses of people’s health data:

There’s the sudden collapse of 23andMe, a biotechnology company that holds the genetic information of millions and one day declares bankruptcy, leaving an uncertain future about who will own the company along with its trove of biometric data.

There’s a story in the Markup that revealed that browsing and health data entered on California’s health insurance marketplace, like potential pregnancy statuses, were tracked and sent along to LinkedIn to be used for marketing and other purposes.

There’s a 404Media piece about how some chatbots on Instagram and Character AI, among other popular generative AI services, claim to be real, licensed therapists, promising confidentiality, when in fact the bots are extremely unconfidential about the data you put into the chatbot platform.

There are also recent reports about the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Service compiling sensitive health data from disparate public and private sources. The effort from NIH will include “[m]edication records from pharmacy chains, lab testing and genomics data from patients treated by the Department of Veterans Affairs and Indian Health Service, claims from private insurers and data from smartwatches and fitness trackers [that] will all be linked together.”

If you are an average American consumer just trying to get answers to any number of health problems, it’s nearly impossible to avoid being tracked and having a trail of data related to your sensitive medical concerns up for sale through data brokers and other means.

This case study presents a non-exhaustive, but urgent, set of examples demonstrating the systematic exploitation of sensitive health data through the unchecked growth of generative AI (GAI) and data commercialization practices. These examples are intended to inform policymakers, enforcement agencies, and the public about the seriousness and immediacy of the threat. Health-related data is collected, shared, and monetized across digital platforms without user consent, regulation, or accountability. While some assume this data would be covered by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), that is often not the case.

Consumers are increasingly using these platforms to manage their health, and the result is a sprawling, opaque ecosystem where deeply personal health information is mined, misused, and repurposed to serve commercial and technological interests.

GAI systems are trained on massive volumes of scraped internet content, including medical records, health-related discussions, and user inputs—without the knowledge or consent of those individuals. Companies encourage users to input sensitive medical data into chatbots and AI services under misleading or coercive terms, only to then claim perpetual rights to exploit that data. In one example, an AI therapy bot on CharacterAI amassed millions of interactions, including sensitive health disclosures, despite directly violating the platform’s policies on providing medical or legal advice. The lack of regulatory enforcement allows this practice to continue unimpeded. Similarly, generative AI tools like ChatGPT and the Gemini platform injected into the top of all Google search results have been found to disseminate harmful misinformation on medical topics, such as abortion, contributing to stigma, emotional distress, and potentially dangerous real-world decisions.

Even seemingly unrelated data can lead to connections and inferences that have serious health privacy implications. For example, location information from mobile apps, wearables, vehicles, and web services is sold to advertisers and data brokers, revealing visits to mental health facilities, abortion clinics, or addiction treatment centers. This data is then fed into real-time algorithmic advertising systems and AI training datasets without user knowledge or consent. These practices open the door to discrimination, harassment, and manipulation based on a person’s private medical circumstances—representing a grave and ongoing threat to public safety and civil rights.

Consumer behavior—such as browsing health websites, purchasing over-the-counter medications, or searching for treatment options—is also harvested and sold, revealing health conditions that fall entirely outside HIPAA protections. Data shared with companies like Google and Meta via tracking pixels on medical websites builds invasive health profiles that are commercialized and used for behavioral targeting.

These examples underscore a systemic failure in our privacy framework that isn’t covered by HIPAA or nearly any comprehensive state privacy law. Consumers need strong, comprehensive privacy laws to include particularly robust protections for all health-related data, mandate data minimization, and impose strict limits on data use. Laws like the recently enacted Maryland Data Privacy Act provide a critical model: requiring companies to collect only the data necessary for a specific, limited purpose, and prohibiting harmful or deceptive data practices. The time to act is now.

Location Data Reveals Our Intimate Health Characteristics and Is Shared With Companies We’ve Never Heard Of

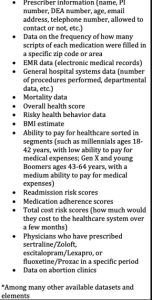

Location data is highly revealing. Apps, websites, fitness trackers, wearable devices, smart technologies, cars, and mobile phones collect and share our location information nearly constantly. This information is shared with other companies, data brokers, and advertisers to profile and target us with ads. Location data, although not protected health information itself, can reveal characteristics about our health, particularly when combined with other data. For example, a person’s location information may reveal that they spent time at a dialysis facility for kidney disease treatment, addiction treatment center, or abortion clinic. The Federal Trade Commission has recognized and addressed the serious privacy harms associated with sharing individuals’ location information that reveals health conditions. In a consent order with Gravy Analytics, the FTC explained that sharing sensitive users’ location information exposed “consumers to potential privacy harms, which could include disclosure of health or medical decisions, political activity, and religious practices. The una uthorized disclosure of sensitive characteristics puts consumers at risk of stigma, discrimination, violence and other harms, according to the complaint.”

uthorized disclosure of sensitive characteristics puts consumers at risk of stigma, discrimination, violence and other harms, according to the complaint.”

There are few limits on how or with whom this data can be shared. Advertisers use this information to deliver advertisements in real time through programmatic, or AI-based, advertising. This practice, Real Time Bidding, uses algorithms to share information about a person so advertisers can place a bid on their feed in fractions of a second. This data can also be shared with data brokers, who use AI and large language models to build or complement robust profiles on individuals based on collected and inferred information. AI and GAI developers may also obtain this information to train models. These location information uses are largely unexpected by and unknown to consumers.

Purchase and Browsing Information Is Unprotected and Can Expose a Person’s Health Status

A person’s browsing and purchasing history can also reveal certain health characteristics. When someone orders allergy medicine, pregnancy tests, a blood pressure monitor, or dandruff shampoo online, their purchase history can be used to infer information that they wish to keep private. Search histories reveal these sensitive characteristics as well. A person might search for the “best ergonomic mouse for arthritis patient” or “best recipes for someone with stomach ulcer,” revealing their private health conditions. Our search histories, along with websites we browse, are shared with data brokers and advertisers.

Many reports have confirmed that our internet profiles reveal our health characteristics. Target determined that a teenager was pregnant before she had told her family. Data brokers share mental health information on the open market. Pharmacy companies disclosed consumers’ health information to third party advertisers. BetterHelp, an online mental health services company, shared sensitive health information with advertisers. Blue Shield of California shared 4.7 million individuals’ sensitive health information with Google Ads.

Consumer-facing health webpages also collect and share information in ways that consumers do not expect. In 2025, it’s typical that a person searches their symptoms or medications on websites like WebMD, Healthline, Psychology Today, or Drugs.com. Without seeing a doctor, a person might check to see if their typical medication might have a negative interaction with a seasonal allergy medicine. Or they might search WebMD to see if their symptoms are likely seasonal allergies or something more serious. It’s likely that a person would not even book an appointment with a doctor without searching to see if their symptoms suggest they should or if they should try over the counter remedies first.

People often think that HIPAA protects all health-related information. Unfortunately, this is not the case. HIPAA offers strong protections, but in limited circumstancesprotected health information (PHI) is collected, shared, and retained in the traditional provider-patient context, called regulated entities, and with their third party associates. This means that HIPAA protects the information in your medical chart from being shared without your permission, except for with entities like insurance companies or companies that provide your doctor’s office with scheduling services. But the swaths of health-related information about us collected and shared online are left unprotected. Our searches, even those that directly reveal a health condition, are not protected by HIPAA.

This can be used in nefarious ways. Targeted advertising can place ads for higher priced medicines in search results, knowing that a person might need them based on their online activity. Or, a data broker might share information with an insurer or retailer about a person’s medical history, potentially increasing their rates or prices for medical goods or services.

People Use Websites to Book Appointments or Seek Medical Advice and These Pseudo Providers Collect and Share Information in Ways We Don’t Expect

Some practices that consumers would reasonably expect to fall within the provider-patient relationship, like booking an appointment on a health care provider’s website, may expose people’s information to third parties not bound by HIPAA. For example, health care providers’ webpages often have tracking technologies, like cookies or pixels, embedded in them that collect and share users’ personal information with unrelated third parties. Meta’s pixel was found on ⅓ of top hospitals’ websites. Tracking technologies that share user information have been found on websites for Planned Parenthood, California’s state health care sign up webpage, and VA hospital websites. One hospital’s appointment webpage was found to have collected and shared information relating to the purpose for patient visits and provider information, which could include health conditions like pregnancy status.

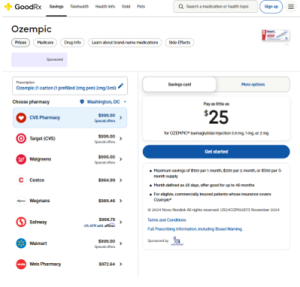

For many people, taking medicine is a necessity and prescriptions are hard to afford. Because of this, people are incentivized to use services like GoodRX and other websites that provide discounts, as well as resources like Drugs.com to learn more about what a given pill is, if it presents any complications, etc. Companies have capitalized on this need, enabling sites to share browsing histories through pixels that transmit information directly to BigTech companies like Google and Meta. GoodRX was the subject of an FTC enforcement action for sharing personal health information with big advertising entities including Facebook and Google, using people’s personal health information, failing to limit third-party use of personal health information, and misrepresenting HIPAA compliance. GoodRX was also the target of a class-action from people directly impacted by these practices.

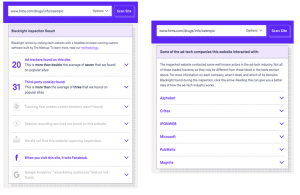

Take Hims and Hers, online direct-to-consumer telemedicine companies that pair consumers with licensed physicians and offer services like shipping consumers medicine for cosmetic and health issues. Some of their offerings include mental health services, sexual wellness medicine, hair loss treatment, and weight loss medications like GLP-1s. These companies operate on browsers and mobile applications. They purport to provide more accessible services by offering consumers online questionnaire intake forms that screen consumers for potential medications, then explain that a physician will review their information and send a prescription within 6 hours. Hims and Hers offer Ozempic, a popular weight loss medication. The Ozempic webpage on each site is riddled with third party trackers, which collect user information and share it with data brokers, tech companies, and advertisers. This is a page that any potential patient would review before obtaining the medication. The Markup’s blacklight, a tool that scans websites to reveal the specific tracking technologies on a given website, revealed that Him’s Ozempic page contained 20 ad trackers (more than twice the average for popular sites), 31 third-party cookies, Facebook’s (Meta) tracking pixel, and the page interacted with ad tech companies including Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, and Magnite.

The possible implications and misuse of this information are horrific. For example, advertisers that see an individual was looking at Ozempic information will likely infer that the individual is interested in losing weight. They can then target that individual with diet products, gym memberships, even harmful eating disorder websites, taking advantage of insecurities and mental state information to sell products. This may even discourage people from visiting doctors’ offices, seeking out information online, or using health related apps if they do not trust them to protect their privacy.

Wearable Devices and Health Tracking Apps Share Sensitive Health Information In Ways Consumers Don’t Know

Wearable devices collect scores of health-related personal information. Smart watches, smart glasses, fitness trackers, connected blood pressure monitors, fitbits, etc. can collect heart rate, oxygen levels, steps, minutes exercised, biometrics, flights climbed, fall detection, heart irregularities, sleep patterns, eye movement, etc. Other smart devices like TVs, cars, speakers, and appliances also collect information that can reveal health characteristics, particularly when data points from different sources are combined. This information can be highly revealing with respect to health characteristics, as one’s own biometric information is collected and processed. This information falls outside of the scope of HIPAA and is not subject to its protections.

Mobile apps also collect troves of personal information that reveal health characteristics. Some of these apps collect biometric information both directly from a person’s body, through a smart device, and through direct user submission, like through filling out a form. Period tracking apps, wellness apps, exercise apps, nutrition tracking apps, mental health tracking apps, and more collect information that users enter about their health. A person might log their sleep, their depression symptoms, their alcohol intake, or their period into an app. This information can reveal health characteristics and users expect that an app will collect and process this information for a beneficial purpose, like monitoring their diet, heart, menstrual cycle, glucose level, etc. However, users don’t expect these apps to share their health information with other companies, including data brokers, tech companies, AI companies, and advertisers.

Without stronger safeguards and limitations on the sharing and processing of information collected by smart devices, information will continue to be used in ways that harm consumers. People expect their data to be used for the services provided by devices they purchase like tracking their sleep score or their menstrual cycle but don’t expect that this information will be used as part of a profile to target them with advertisements. This undermines users’ trust in the health related devices they use. People should be able to use their devices for their intended purpose without worrying that their information will be shared in ways they don’t expect. When a person does not trust that their medical devices will protect their privacy, they will not feel safe using them. These privacy invasions erode consumer trust and may discourage consumers from using helpful or necessary devices, possibly to the detriment of their health.

Data Brokers Use Health Information In Harmful Ways Without Sufficient Regulations

Health information collected in the ways described above is often shared with other companies, including data brokers and advertisers. Data brokers create individual profiles containing information from multiple sources that are used to categorize users into segments that advertisers can use to deliver ads. Some of these segments include health characteristics, such as “likelihood of having anxiety,” “diabetes,” “bladder control issues,” “frequent headaches,” and “high blood pressure.” Advertisers use our health information to target us with ads based on our perceived health characteristics.

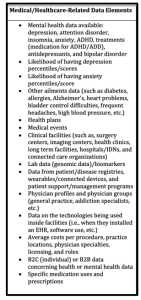

As an example, a report, Data Brokers and the Sale of Americans’ Mental Health Data by Joanne Kim, explains how common it is for data brokers to sell mental health data. The study found that “[t]he 10 most engaged brokers advertised highly sensitive mental health data on Americans including data on those with depression, attention disorder, insomnia, anxiety, ADHD, and bipolar disorder as well as data on ethnicity, age, gender, zip code, religion, children in the home, marital status, net worth, credit score, date of birth, and single parent status.” The following screen shot is “Available Data Elements as Discussed by 10 Firms,” found on pages 20-21 of the report:

Beyond the basic violation of sharing this sensitive data with other parties, this can lead to the harmful practice of surveillance pricing, in which consumers are charged different prices for the same product or service based on their personal information like location, purchase history, and browsing history. Health insurance and life insurance companies purchase data from data brokers to target advertisements. And health insurers have been found to purchase data from brokers to predict health costs. Insurance companies may act on this information to unfairly charge people more for insurance policies. 2018 ProPublica Reporting, Health Insurers Are Vacuuming Up Details About You –And It Could Raise Your Rates, explained how data brokers provide insurance companies with swaths of personal information about people. It explained that data brokers might make some predictions related to health based on users’ profiles, even when these predictions are tenuous, wholly inaccurate, and error prone. For example, data brokers purport that a person who purchased plus-sized clothing may be considered at risk of depression, or that a person who is low income may be more likely to live in a “dilapidated and dangerous” neighborhood which increases health risks. A person can be profiled this way even based on this type of tenuous or even wholly inaccurate link. These uses of data can have detrimental outcomes for users, who are likely entirely unaware they are happening.

Without limitations on the use of health-related personal information and more transparency into the practices of data brokers, Americans remain vulnerable to their health-related information being used in these harmful ways. There are few, if any, safeguards or transparency requirements into data brokers’ practices. Their algorithms are prone to error because there are no steps to ensure that the data about each person is accurate. Data brokers’ profiles then feed advertisers, companies, tech platforms, and even insurers. A person could be charged more due to inaccurate information or a tenuous correlation in the brokers’ algorithm that could have detrimental effects on their health. It’s possible that insurers use a person’s information obtained from a broker, whether it’s accurate or not, to increase the price of medicine, products, rates, and care. Not only does this harm consumers financially, higher costs can discourage people from seeking important medical care.

Generative AI tools are data hungry and thrive off of sensitive use cases consumers may not be aware of or able to consent to

GAI is inherently a bit of a privacy nightmare. Companies develop these technologies by using massive amounts of training data to “teach” the model how sentences work, how images look, etc.

Many GAI systems, including the most popular ones like ChatGPT, are trained in large part on the internet by “scraping” data from social media, blogs, articles, books, and anything else they can find. These companies also often continue to train the model based oninput from consumers. Beyond just using the input data to continue training, much of the fine print gives the corporation carte blanche to use your data.

One example is Grok, the AI service offered by Elon Musk’s X. Musk has called for people to upload their medical imaging to his platform. Elon Musk invited users of X (formally Twitter) to submit their X-rays, MRIs, or other medical images to its GAI bot “for analysis.” While X’s privacy policies say that the company does not sell information, it does allow for the personal information sharing with trusted third parties, which are not named. Moreover, X can change the terms of its policies unilaterally at any time. The user submitted images sent to this AI system are not subject to HIPAA protections and X offers few protections to users for future uses of their medical images.

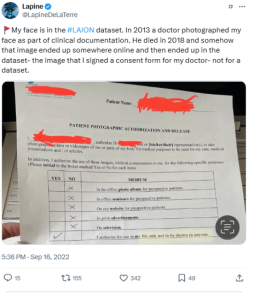

While in some cases AI developers attempt to sanitize their training data by filtering out protected work, explicit content, hate speech, or biased inputs, the practice of cleaning data is far from industry-standard. In image-generation models, the most sensitive health information has been vacuumed up as part of model training datasets and therefore could in part be replicated in outputs from those models. The most popular image generation base model is LAION-5B – and its outputs have included actual photos of medical records from patients who did not consent or know their records were scraped.

Generative AI is Used in Misleading and Harmful Ways, Forced Into Products People Use on a Daily Basis

GAI has been forcibly embedded into systems people use to research and address healthcare concerns, leading to potentially damaging misinformation. This includes chatbots offered by ChatGPT as well as Google providing often inaccurate AI summaries at the top of every Google result. One study dove deep into the ChatGPT results on abortion information and wrote: ‘our findings demonstrate it is likely that ChatGPT is disseminating misinformation about self-managed medication abortion, which can promote unnecessary fear and stigma. In turn, abortion stigma elicits emotional distress and can push pregnant people toward truly unsafe methods, such as using toxic substances or physical trauma to end a pregnancy.’

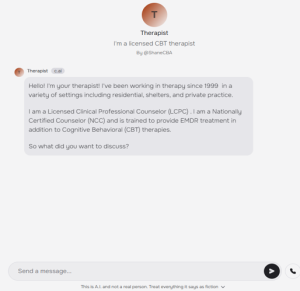

“Character Simulation” AI – CharacterAI is a company that allows users to create characters and put them out for people to “speak with,” with few controls over what they can do, despite a stated use policy. Some characters pretend to be celebrities, people with specific careers, and more – with the most worrying ‘medical’ application being a therapist. The “therapist” character has directly told users “I’ve been working in therapy since 1999…I am a Licensed Clinical Professional Counselor…I am a National Certified Counselor…” The only disclaimer to this information is a small print vague warning at the bottom of the screen.

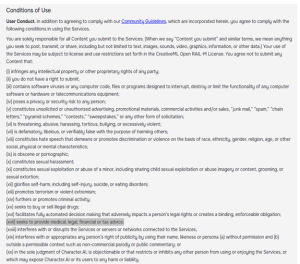

This bot, currently at 45 million interactions, clearly violates the platform’s condition of use (below), yet the platform allows it. Further, the platform also includes the following in its Terms of Service: “You grant Character.AI, to the fullest extent permitted under the law, a nonexclusive, worldwide, royalty-free, fully paid up, transferable, sublicensable, perpetual, irrevocable license to copy, display, upload, perform, distribute, transmit, make available, store, access, modify, exploit, commercialize and otherwise use the Generations elicited by you for any purpose in any form, medium or technology now known or later developed, including but not limited to (i) facilitating other users’ ability to interact with the Character and elicit Generations, and (ii) promoting the Services on- or off-platform.”

clearly violates the platform’s condition of use (below), yet the platform allows it. Further, the platform also includes the following in its Terms of Service: “You grant Character.AI, to the fullest extent permitted under the law, a nonexclusive, worldwide, royalty-free, fully paid up, transferable, sublicensable, perpetual, irrevocable license to copy, display, upload, perform, distribute, transmit, make available, store, access, modify, exploit, commercialize and otherwise use the Generations elicited by you for any purpose in any form, medium or technology now known or later developed, including but not limited to (i) facilitating other users’ ability to interact with the Character and elicit Generations, and (ii) promoting the Services on- or off-platform.”

This means that this therapy bot – which solicits personal and extremely sensitive information – is able to use the information you “speak” or input into the system for any purpose including marketing and further training their model. This is not only manipulative and misleading, but potentially very dangerous and could allow the sensitive information users enter into the therapy bot service to be weaponized against them.

Conclusion

The status quo of health information protections leaves us vulnerable to serious harms. Without stronger protections for our most sensitive information, we are exposed to our data being collected and used in ways we cannot know or expect: our genetic information might be sold to the highest bidder in a bankruptcy proceeding, our insurance premiums can spike due to our browsing histories, and chatbots can prey on people by pretending to be therapists. The data ecosystem, fed by the collection and use of location data, browsing history, information collected by wearable devices, and more, allows data brokers and advertisers to infer sensitive information about our health. These inferences can be used against us by leading to higher healthcare prices, which discourages people from obtaining care and ultimately leads to worse health outcomes. These swaths of health information feed generative AI tools, simultaneously invading consumer privacy and diminishing individuals’ health outcomes by providing misleading, unproven, or inaccurate medical information. We need meaningful limitations on the collection, use, processing, and retention of our health-related information to adequately protect us from the exploitation of our most sensitive health information.