The survey results we report today reflect a firm commitment to and a demand for balanced democratic discourse in our nation. These sentiments reinforce the bold aspiration for the First Amendment that was articulated by the Supreme Court over the course of the twentieth century. The unique characteristics of broadcast media were recognized by the Congress early in the century and the airwaves (radio spectrum) were defined as a public resource. Public policies to ensure that the immense power of the new media promotes democratic debate and the free flow of information have been repeatedly upheld by the Supreme Court.

Because the “widest possible dissemination of information from diverse and antagonistic sources is essential to the welfare of the public,”2 the court has found that Congress has the right to ensure that the electronic media serve the public interest. Consequently, limits and obligations on media owners – limitations on ownership and owner rights, on programming aired, as well as obligations to air specific types of programming – do not violate the First Amendment.

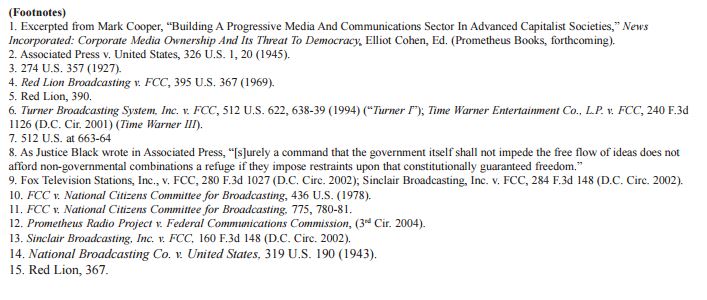

The objective of discourse is to draw citizens into participation in civic affairs. “The greatest menace to freedom is an inert people; that public discussion is a political duty; and that this should be a fundamental principle of American government.”3 In Red Lion, the seminal television case, the Court expressed a similar sentiment, noting that “speech concerning public affairs is more than self-expression; it is the essence of self-government.”4 The discourse must be full and open because “[i]t is the right of the viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters, which is paramount…the right of the public to receive suitable access to social, political, aesthetic, moral and other ideas and experiences which is crucial here. [T]he ‘public interest’ in broadcasting clearly encompasses the presentation of vigorous debate of controversial issues of importance and concern to the public.”5 Turner I, 6 frames it in equally aggressive terms stating that “[a] diverse and robust marketplace of ideas is the foundation of our democracy.”7

Moreover, the First Amendment is not limited to preventing government from impeding the free flow of ideas.8 The decisions in the cases spawned by the Telecommunications Act of 1996, Fox v. FCC and Sinclair Broadcast Group v. FCC, reiterate the principle that restraints on the economic interests of licensees are legitimate in the effort to promote the public’s interest in diversity.9

In order to ensure that discourse is balanced, it is permissible for policy to prevent undue concentration of economic power and excessive influence. In FCC v. National Citizens Committee for Broadcasting,10 a 1978 case, the court upheld limitations on ownership “on the theory that diversification of mass media ownership serves the public interest by promoting diversity of program and service viewpoints, as well as by preventing undue concentration of economic power.”11 It was this very language that the Third Circuit Court earlier this year in overturning the new Federal Communications Commission rules on media ownership.12

In 2002, the D.C. Circuit Court in Sinclair restated the broad purpose in promoting the public interest when it stated “the greater the diversity of ownership in a particular area, the less chance there is that a single person or group can have an inordinate effect, in a political, editorial, or similar programming sense, on public opinion at the regional level.”13

Starting with a 1943 radio case, National Broadcasting Co. v. United States, 14 and continuing through the most recent cases, the Supreme Court found that “where there are substantially more individuals who want to broadcast than there are frequencies to allocate, it is idle to posit an unabridgeable First Amendment right to broadcast comparable to the right of every individual to speak, write, or publish.”15 In fact, in the Sinclair Broadcast Group v. FCC decision the D.C. Circuit Court went to considerable lengths to reject Sinclair’s claim that its First Amendment rights had been harmed by the duopoly rule.

[B]ecause there is no unabridgeable First Amendment right comparable to the right of every individual to speak, write or publish, to hold a broadcast license, Sinclair does not have a First Amendment right to hold a broadcast license where it would not, under the Local Ownership Order, satisfy the public interest. In NCCB the Supreme Court upheld an ownership restriction analogous to the Local Ownership Order, based on the same reasons of diversity and competition, in recognition that such an ownership limitation significantly furthers the First Amendment interest in a robust exchange of viewpoints.

The adjectives used by the courts describe a bold aspiration for the First Amendment articulated over 75 years. The goal is clear, uninhibited, robust, vigorous debate about all important issues among citizens who have access to the necessary information beyond what merely commercial interests would provide and whose voices can be heard, free of undue concentration of economic power or the inordinate effect through editorial control of a single person or group. Since the number of broadcast licenses remains vastly smaller than the number of citizen speakers, the public interest continues to demand, among other things, the dispersion or ownership and vigilance to ensure fair presentation of diverse points of view.

It is reassuring to find that public opinion supports fair play in the media and public responsibilities of broadcaster, consistent with a long line of Supreme Court cases that has upheld limits on media ownership and other rules to ensure a robust exchange of views. Ultimately, however, it is the vigilance of each and every citizen that is the guarantor of our democracy and the grass roots opposition to Sinclair’s high-handed behavior should put all broadcasters on notice that the airwaves must be used to promote the public interest.

Mark Cooper (301) 384-2204, email – markcooper@aol.com