Authors: Ethan Weiland, Adam Rust

Overdraft fees transfer billions of dollars of wealth from regular people to banks every year.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) recently introduced a rule that levels the playing field between banks and their customers. Congress must protect the rule.

The rule establishes a new framework for how banks with over $10 billion in assets price their overdraft fees. It creates three options.

- Banks can charge $5 per overdraft. Through research, the CFPB determined that the cost to banks for an overdraft is roughly five dollars, based on the expenses they experience to reverse funds, notify the account holder, and cover the debt.

- If a bank can provide evidence that its actual costs are higher, it can charge more up to an amount equal to its costs.

- Banks can offer an overdraft line of credit consistent with the rules applicable to other loans. This means they must disclose the cost of credit, provide periodic statements and repayment periods, and assess a borrower’s ability to repay a debt.

Senator Tim Scott (R-NC) introduced a Congressional Review Act (CRA) notice of disapproval to reverse the rule (S.J. Res, 28). On March 27th, the resolution passed in the Senate 51-47, with bipartisan opposition. The House of Representatives may consider the companion bill as soon as Tuesday, April 8th. If the CRA passes, the CFPB is prohibited forever from introducing a “substantially similar” rule.

The CRA is a blunt tool for policymaking. It takes years to craft a rule through notice-and-comment, and only a quick up-or-down vote can cancel it and close the door on future policymaking.

The Consumer Federation of America examined publicly available data to document the amount the banks affected by this rule receive from overdraft fees.

The banks in the data cumulatively received $4,883,630,000 (approximately $5 billion) from overdraft fees in 2024. Table 1 displays the ten banks that charged the most from overdrafts in 2024. JPMorgan Chase led the way with $1.028 billion, and Wells Fargo was not far behind at $1 billion. These two banks far outpaced every other bank.

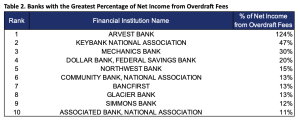

Next, we review bank overdraft fee income in the context of the institution’s size. As some banks have significantly greater assets than others, this lens pinpoints which banks rely most on overdraft fees, controlling for overall net income.

Table 2 displays the top ten banks by the percentage of their net income that came from overdraft fees in 2024. First is Arvest Bank (owned by the Walton family of Walmart), one of the plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed against the overdraft rule in the United States District Court for the Southern District of Mississippi. Their ratio is greater than 100% because our measure uses net income.

The lack of overlap between the institutions in the two tables demonstrates the importance of accounting for size. While JP Morgan made the most from overdraft fees in absolute terms, it was only 2% of their net income in 2024. The data show why the banking industry opposes the overdraft rule: charging overdraft fees is lucrative.

Some banks have voluntarily reformed their overdraft practices. Citigroup and Capital One do not charge overdraft or non-sufficient funds fees. Bank of America limits its overdraft fees to ten dollars and limits the types of transactions that can trigger an overdraft fee. Accordingly, overdraft revenue is equivalent to approximately one-half of one percent of Bank of America’s net income.

Others have developed small-dollar credit products that would comply with the CFPB’s overdraft line of credit terms.

Important points to understand about the CFPB’s rule:

The rule will help consumers of the covered banks struggling to make ends meet. Almost 40 percent of American households have less than $400 in liquid assets. By reversing the overdraft rule, S.J. Res 18 would eliminate the prospect of a checking account with a $5 overdraft fee and discourage banks from offering an alternative low-cost small-dollar line of credit. Many households might be able to pay a $5 overdraft fee and still afford groceries but would be hungry if their bank charted a $35 overdraft fee.

The rule will not affect the operations of community banks. The narrowly tailored rule applies only to banks and credit unions with more than $10 billion in assets. As a result, the rule excludes approximately 97 percent of insured depositories from its scope.

The rule is not overly prescriptive. Banks can offer a traditional overdraft at a price consistent with their service costs. The CFPB has set a $5 fee, but if banks can “show their math” that a larger number is warranted, they can do that. Alternatively, banks can offer an overdraft line of credit that conforms to lending regulations. They can charge interest. Consumers will receive periodic statements, clear pricing disclosures, and other beneficial protections.

Banks charge billions in overdraft fees. Banks and credit unions with over $1 billion in assets charged $7.7 billion in overdraft and NSF fees in 2022 and $5.8 billion in 2023. Over the five years before the pandemic, total overdraft fee charges ranged from $11.8 billion to $12.6 billion per year. This analysis reveals that Wells Fargo and JPMorgan Chase charged more than $1 billion in overdraft fees. Even without overdraft fees, these two institutions would have earned more than $21.6 and $51.5 billion in 2024, respectively.

Overdraft fees undermine trust in banking. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s bi-annual Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households consistently finds that unbanked consumers’ fear of surprise overdrafts and NSF fees is a primary reason to support their decision not to use a bank.

Conclusion

The data show why the industry opposes the overdraft rule: charging overdraft fees is a lucrative business. These outcomes contradict the purpose of banking. Banks should be in the business of making loans, facilitating payments, and taking deposits – not enriching themselves with junk fees.

We call on Congress to uphold the CFPB rule.

About our methods

The data used for this analysis includes information on banks’ income from overdraft fees in 2024. The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC) publishes the information in quarterly call reports.

Many financial institutions are required by law to provide information on their income from “service fees” to the federal government. Service fees include overdraft fees, maintenance fees, ATM fees, and other fees. This data (in the form of what is called a “Call Report”) are published each quarter by the Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC).

The data on service fees are found in the following variables:

- RIADH032 – Overdraft Fees – “Consumer overdraft-related service charges levied on those transaction account and non-transaction savings account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.”

- RIADH033 – Maintenance Fees – “Consumer account periodic maintenance charges levied on those transaction account and non-transaction savings account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.”

- RIADH034 – ATM Fees – “Consumer customer automated teller machine (ATM) fees levied on those transaction account and non-transaction savings account deposit products intended primarily for individuals for personal, household, or family use.”

- RIADH035 – Other Service Fees – “All other service charges on deposit accounts.”

While the FFIEC’s data covers all banks with more than $1 billion in assets, we restrict the data in this analysis to banks that reported more than $10 billion in assets during any quarter in 2024, consistent with the rule’s scope. The data does not include credit unions.