By Thomas Gremillion and Ethan Weiland, Consumer Federation of America

A month of “shock and awe” has taken a toll on our collective attention span. But let’s not forget how we got here. Voters ranked inflation, felt most acutely in rising grocery prices, as the most important issue in the 2024 presidential election. So far in the Trump 2.0 tenure, inflation has worsened, with egg prices reaching an all-time high. And that trend is likely to continue, according to our analysis of historical data.

Much of the debate around food prices has focused on policies related to tariffs and immigration, which may already be helping to push up food prices. The Administration’s primary price reduction strategy—eliminating environmental protections and other regulatory impediments to fossil fuels —will take time to implement, and experts question how much it would affect energy production even if carried out to its fullest potential. just

But while Trump 2.0 may not yet have done anything explicitly geared towards lowering food prices, it has already taken decisive and meaningful action to trample norms, disregard the law, and engage in breathtaking corruption. As legal challenges continue to mount, the Administration’s disregard for court orders is now “one step short of outright defiance” and the specter of a constitutional crisis looms. If history is any indication, these actions—with perhaps the most notorious so far being Trump’s decision to pardon all January 6 rioters, including hundreds guilty of assaulting police—will make food more expensive.

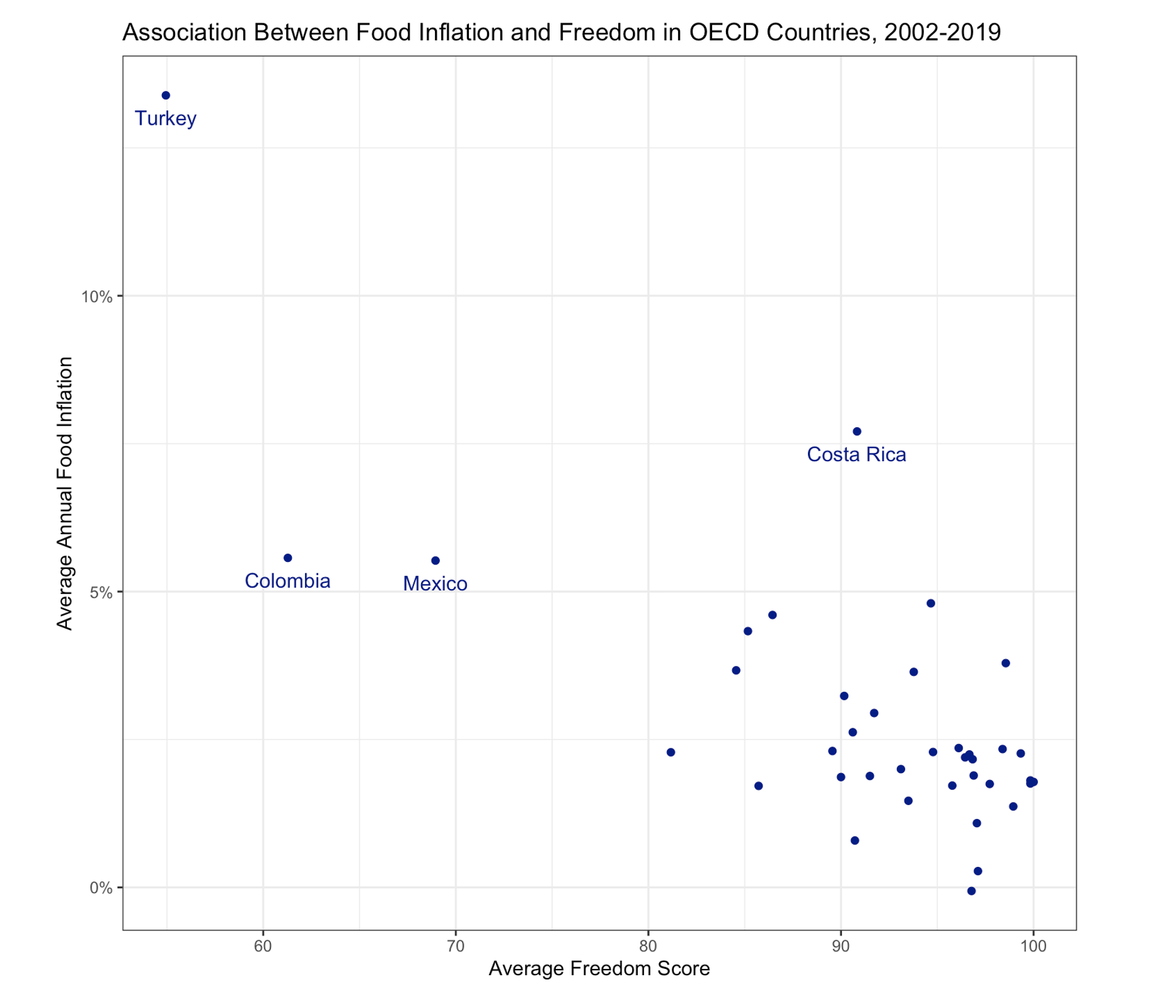

Our analysis compares food inflation data with data from Freedom House, an organization founded in 1941 that scores countries around the world from 0 (least free-Chinese occupied Tibet) to 100 (most free–Finland) based on various measure of freedom, such as fairness of elections, rule of law, and freedom of expression. Countries get a lower score if, for example, “nonstate actors, including criminal gangs and insurgent groups, interfere with or prevent elected representatives from adopting and implementing legislation and making meaningful policy decisions.”

Trump’s pardons “increase the risk of future political violence,” as Freedom House explained in a press release, because “they send the message that supporters of the president who carry out such assaults on his behalf will be shielded from punishment.” In other words, Trump’s pardons exacerbate a growing threat of political violence that already exerts a powerful influence on lawmakers around the country, especially Republican lawmakers. Indeed, congressional candidates felt compelled to increase campaign expenditures on security by 500% in the 2022 midterms compared to two years before, and the Capitol Police reported a surge in threats—nearly 10,000—against members of Congress and their families in 2024.

What happens in countries where such threats are allowed to fester? There is less economic growth, according to last year’s Nobel prize winners. Also, more expensive food.

Our analysis shows that among the relatively rich member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), lower Freedom House scores are strongly correlated (ρ=-0.742) with rising food prices during the roughly two decades (2002-2019) leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic. The average cumulative food inflation in countries where the freedom score decreased during this period was 39% points higher than in countries where freedom stayed the same or improved. Turkey, the least free OECD country, also experienced the highest average annual food inflation.

Source: CFA analysis of OECD and Freedom House data.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has become more like Turkey, with partisan rancor driving the nation’s “freedom score” from a high of 94 in 2010, to a low of 83, where we have remained since the first Trump Administration.

Could high inflation lead voters to elect a strongman who then reigns in grocery prices, as Trump has promised to do? The data suggest otherwise. Food inflation tends to be higher in the years following a decrease in freedom—an average 3.18% compared to 2.69% in years following unchanged or improved scores. And in more years than not following a decline in freedom, the rate of inflation increased from the year before.

Why do food prices tend to rise as freedom declines? Bad policy explains part of the effect. Reasonable people will always disagree about questions like the appropriate level of immigration or international trade flows. But the democratic process helps to identify areas of mutual benefit, so that all policies—whatever their ultimate objective—avoid unnecessary disruption and waste.

By contrast, rule by fiat, as exemplified by Elon Musk’s DOGE wrecking ball, may do lasting damage before encountering meaningful resistance. Consider that with an ongoing bird flu outbreak driving egg prices to record highs, DOGE summarily fired federal workers responsible for containing the outbreak. An outcry from some Republican lawmakers led USDA to rescind the terminations, but this was the exception to the rule. Other DOGE cuts have gone unchallenged, and could easily lead to more food inflation. Arbitrary dismissals at FDA and CDC, for example, are likely to hamper responses to foodborne illness outbreaks, undermining consumer confidence in the food supply and increasing the costs associated with food recalls.

Another reason food prices soar in less free societies is corruption. When elected representatives are too scared to break ranks, moneyed interests take advantage behind the scenes to push for ever more craven self-dealing. In the second Trump Administration, industry lobbyists now find many of their former K street colleagues operating the levers of power. The outrageous $Trump coin grift sends the message that appointees will pay little price for ethical indiscretions, a message reinforced by the Administration’s dismissal of 17 Inspectors General. The absence of these watchdogs has also conveniently created space for the Administration to make unsubstantiated claims about how much DOGE is saving taxpayers.

Already, polling shows that the public is turning on DOGE. Trump 2.0 can still moderate its approach, pull back from the radical “unitary executive theory” that has animated its most egregious overreaches, and even take effective action on food prices. Trump’s Federal Trade Commission, for example, could heed calls to open an investigation into anti-competitive practices among large egg producers. It could build on the FTC’s successful challenge to the proposed Kroger-Albertson’s grocery merger, and continue chipping away at the monopoly conditions that enabled food companies to log record profits as food prices soared during the pandemic.

But don’t hold your breath. As democratic norms erode, narrow special interests will find more opportunities to hijack policymaking. And the rest of us may find that we are not eating as well as we once did.

Thomas Gremillion is Director of Food Policy and Ethan Weiland is a Research Associate for the Consumer Federation of America (@CFAFoodPolicy), an association of non-profit consumer organizations established in 1968 to advance the consumer interest through research, advocacy, and education.