Recently the Biden Administration released an analysis of manufacturing in the United States. Increases in so-called “advanced manufacturing” investments—the creation or expansion of factories making things like semiconductors and renewable energy technology—accounted for the bulk of the growth. According to the Administration, this growth shows that recent tax breaks and other incentives passed by Congress are paying dividends.

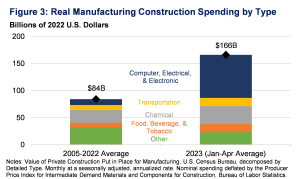

I will let others debate the merits of those policies. In this blog, I would like to draw attention to another aspect of the recent manufacturing statistics: the growth in what the Administration dubs “food/beverage manufacturing.” According to the Administration’s report, while “the computer/electronic” segment drove manufacturing growth over the past year, “construction for chemical, transportation, and food/beverage manufacturing is also up from 2022,” and in fact, a chart in the report (see below) shows that manufacturing construction grew in the “Food, Beverage, & Tobacco” sector more than anywhere other than in the “computer/electronic” sector.

What is this new food and beverage manufacturing? Disturbingly, growth in “Tobacco” manufacturing accounts for almost all of the growth in the “Food Products” sector–$3.966 billion of a $4.277 billion—between March of 2022 and 2023, according to Census data. This growth is a bit of a head scratcher considering that cigarette smoking rates reached an all-time low last year. On the other hand, use of electronic cigarettes has risen, and cannabis use has been soaring, although it’s not clear whether the Census Bureau has lumped that manufacturing activity under “Tobacco.”

The next biggest growth industry in the sector is “Beverages,” accounting for over $2 billion of increased shipment value. This growth reflects a continuation of drinking trends that began during the pandemic, which have coincided with a steep increase in alcohol-related deaths, particularly among women.

By contrast, manufacturing shipments of “food products” rose just 1.8%. Shipments of “meat, poultry, and seafood products” actually declined 1.8%, with “dairy products” and “grain and oilseed milling” increasing modestly at 3.5% and 4.8%, respectively.

The decline in meat processing shipments is notable because that category accounts for the largest chunk of the “food manufacturing” pie. However, meat processing does not generate a lot of “value added.” According to an earlier Commerce Department report, “in 2012, value added accounted for 39 percent of the total value of food, beverage, and tobacco product shipments. The other 61 percent consists of materials and inputs from other industries, such as livestock or crops, or plastic used for packaging.” Of course, businesses want to create value, in order to generate profit, and so one might expect that investment would flow to the sectors of the food manufacturing sector that generate the most value added.

In fact, the latest numbers on alcohol and tobacco suggest that may be happening. As a proportion of shipment values, the products that create the most added value are tobacco (84%), key components of ultra-processed foods (“flavoring syrup and concentrates” (75%)), and alcoholic beverages (specifically, wineries (63%), breweries (66%), and distilleries (67%)). Among other food products, the manufacture of “bread and bakery products” (58%), snack foods (54%), and breakfast cereals (51%) create a lot of value. By contrast, “animal slaughter and processing” adds 22% value, and “cheese” production adds just 21% value.

This data suggests that the invisible hand of the market may encourage a surfeit of tobacco, booze, and junk food consumption. In light of American’s declining life expectancy, we might wonder whether public policy should be doing more to counter the drive for profit and economic growth in the food sector. There are many good ideas about how to encourage production of foods and infrastructure that will expand access to a healthy diet for the millions of Americans who currently experience nutrition insecurity, and to its credit, the Biden Administration is pursuing many of them. However, these efforts will continue amidst a larger backdrop of celebrating economic growth for growth’s sake.

It is axiomatic that what’s measured matters. For all of the heartache that came with COVID-19, the pandemic unified us around a common set of objectives. As the number of deaths and reported infections declined, we breathed a collective sigh of relief. When they spiked, we shared a common dread of a return to lockdowns, school closures, and cancelled visits.

As a new normal sets in, public health metrics have once again taken a backseat. Economic indicators, rather than measures of public health, have returned to prominence as the measure of our collective well-being. This makes sense, to a degree. Economic recessions tend to increase unemployment, poverty, and other societal ills that closely align with the overall levels of well-being. But the health of the economy and society sometimes diverge. As Robert F. Kennedy famously told supporters in 1968, economic output “can tell us everything about America except why we are proud that we are Americans.” Lately his words ring truer than ever.